Don’t fancy I am going to speak of the “ happy land ”of which Richard Weaver1 sings so well, through the medium of the hymn, so joyous with its “away and away” to where many of us, it is to be hoped, have mothers, and sisters, and brothers. Nor will the people of Edinburgh be ignorant of the meaning of the title of my present reminiscence. Yet many may not know the “ happy land ” I allude to—not other than that large tenement in Leith Wynd, not far from the top, composed of a number of houses, led to by a long stone-stair,—the steps of which are worn into inequalities by the myriads of feet, tiny and large, light and heavy, steady and unsteady, which have passed up and down so long,—and divided into numerous dens, inhabited by thieves, robbers, thimblers, pickpockets, abandoned women, drunken destitutes, and here and there chance-begotten brats, squalling with hunger, or lying dead for days after they should have been buried. Well do I know every hole and comer of it, and so well that I shrink from a description of it, which at the best would be only a mass of blotches—not a picture, only coarse cloth and dingy paint. Some people may have a notion of a “stew;” but the Happy Land is a great conglomeration of stews; so that the scenes, the doings, the swearings, the fights, the drunken brawls, the prostitutions, the blasphemies, the cruelties, and the robberies, which you figure of various houses removed by distance, are often all going on at the same moment, and with no more screens or barriers to hide the shame than thin lath walls and crazy doors—often, indeed, without any division at all. Yet all the people who inhabit this accumulation of dens understand each other. It is a world by itself, with no law ruling except force, no compunction except fear, no religion except that of the devil. They laugh at every thing that is fair and good, and transfer the natural feelings due to these over to evil; and, then, there’s not a whit of effort in all this—to them it is perfectly natural. And I’m not sure if they do not consider the outside world over in the NewTown a very tame affair, not worth living for.

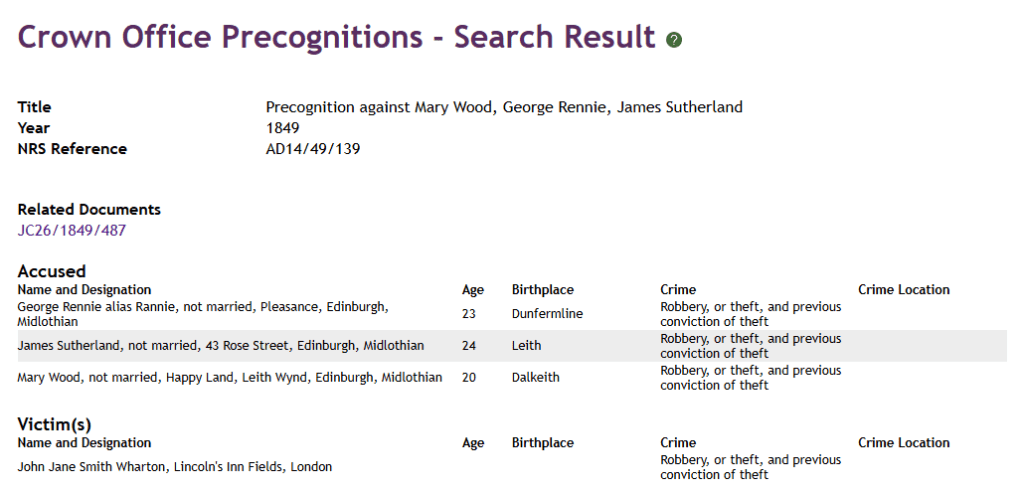

In the third storey of the huge tenement, as you go into the right, there was a section of this little world, occupied by a young, stout, and fair hizzy, called Mary Wood, about twenty years of age. She was well known, not only in the Happy Land itself, but in Princes Street, where she was often seen walking as demurely under her fashionable bonnet as any of the young ladies from the houses in the New Town. Her section was very limited, consisting only of a small room, containing a bed, a table, a chair or two, a looking-glass2 of course, and a trunk for her fineries, not forgetting “ the red saucer.” Immediately off this room was a closet, with no means of light, excepting one or two auger-bored holes, intended for gratifying any one taking up his station there by a look of what was going on in the room. These two apartments formed the castle of this enchantress, and the scene of a plot—not uncommon then—entered into by Mary and two strong ruffians of the names of George Renny and James Stevenson. The conspiracy was not

so complicated as it was bold, dastardly, and cruel Mary was to go out in her most seductive dress, and endeavour to entice in any gentleman likely to have a gold watch and money on him, and when she had succeeded in this, the two bullies, as they have been called, who, on a signal of her approach, had previously betaken themselves to the closet, were, when they considered all matters ripe, to rush out, seize the victim, and rob him.

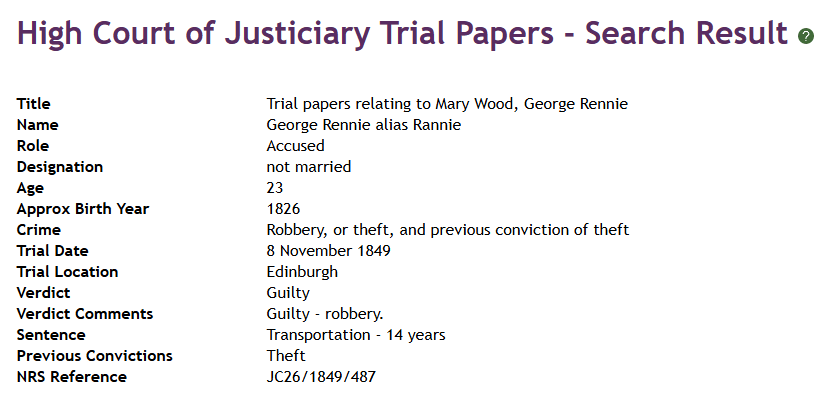

This conspiracy, I had reason to suspect, had been carried on for some time with considerable success, and without our being applied to by the sufferers, many of whom were anxious to conceal their imprudence, and consented rather to lose their watches than expose their character. One night, the 9th of August 1849, our damsel was trying her fortune in Princes Street, while Renny and Stevenson were waiting, ready for their work when the time came. About twelve o’clock, she fascinated a likely “ cully3,” or “ colley,” as the Scotch women say, with perhaps more humour than they wot of—a gentleman of the name of W n, from London, who, little knowing the character of the “happy land” to which he was destined, agreed to accompany her home. In a short time she had him all safe. Mistress of her trade, she was all blandishments to the happy Englishman, who, after all deductions for the squalor of her dwelling, could probably not have picked up a woman better qualified to please; but no sooner had he made preparations for departing, than the gentlemen of the dark closet rushed out upon him, laid him on his back, took from him a gold watch and chain, with fifteen sovereigns, and everything they could rifle; but, most unkind cut of all, the enchantress Mary helped them in their work of robbery, pulling off his fingers two valuable rings, which, a little before, she was praising to him with much admiration. I afterwards ascertained that the struggle was a desperate one, no doubt owing to the value of the property inflaming the

one party, and nerving the other.

When allowed to depart, Mr W n, much injured, and greatly alarmed, rushed downstairs, almost breaking his neck in the descent, and went direct to the Police- office, where he gave a rapid account of the transaction, as well as a description of the parties. The case was one for me, and, about one o’clock, I was roused out of my sleep to catch these robbers. I recollect I was much wearied that day, and was in no humour for a midnight hunt, exhausted, as I had been, by late hours.

I was, notwithstanding, dressed in a moment. I went first to see the gentleman, who seemed inclined to lose more time by a description. I told him it was of no use, for that I knew the men perfectly. I had, indeed, seen them in company with Mary, who was familiar to me, and knew that they were her special retainers. The difficulty was to know where to find them, and get hold of the money, but I had confidence enough to tell Mr W n that, if he would remain for a time in the office, I would bring the robbers to him. As for Mary, she had been taken up about the time I was called, but she had no money on her—the whole having been carried off by the robbers. My task was arduous enough, for, although I knew their haunts, the places were not few, and would likely be avoided. I tried many without success, and was beginning to repent of my promise to Mr W n, when I bethought me of a lodging-house at the West Port, occupied by a man of the name of GoodalL Thither I went.

It was now about four in the morning, and having rapped, I was answered from behind the door by Goodall.

_ “ Did two men come to your house this morning to lodge 1” was my question. “Yes,” replied he, as he opened the door, probably knowing my voice.

“ Well, I think they will be the men I want.” “ But you’re too soon,” said Goodall, with a kind of laugh. “Why?” “ Because it’s only four, and they told me they were not to be wakened till five.

“ That’s a pity,” said I; “ but they will excuse you, and as for me, why they set me up at one, so I’m quits with them there. Shew me into their room.”

I then beckoned the constable I had with me; and, preceded by Goodall, we were led to the side of the bed where lay the very men. I held Goodall’s candle over their faces, and saw the effect I produced upon them—not that I augured from their surprise and dismay that they had done this deed, for I knew I was a terror to them at any time, but that I liked to enjoy my advantage. “ Get up,” said I, “and go with me; ” so sure of my men, that I did not even put them to the question. And then broke in Goodall again with his humour— “Ye see, you’re not to blame me, my lads. It’s only four, but Mr M’Levy says you were the cause of wakening him at one.” These men, who, four hours before, were throttling an innocent gentleman, were now dumb and docile; nay, they were simple,—for Renny, when getting out of bed, let slip— “You’ll not find either the watch or the sovereigns on me, anyhow.”

Stevenson looked daggers at his friend.

“ Why, man,” said I, “ Renny has done no more than

I have made others do, by simply holding my peace; and he has done you no harm either by his mistake, for I can prove that you and Mary Wood robbed the gentleman four hours ago in the Happy Land.”

“ D—n the Happy Land,” cried Stevenson, still enraged at his friend. “ I never found any happiness in it, nor money either.”

“ D—n the Happy Land ! ” said Goodall, again wishing to be witty. “ Lord save us! that’s a terrible oath against a place we are all doing our best to get to. The

very children sing, ‘ Come to yon happy land,’ and you curse it.”

I could scarcely keep from laughing, even in the midst of my impatience, at the keeper of this famous resort for all moral waifs thus reproving, by his mirth, his children, —so many of whom came from that Happy Land. Of course, he had reason to bless it, and did it in his own way of humour—a habit of his.

“ Quick,” said I, as the putting on of the clothes proceeded slowly. “ Mr W n is waiting for you.” Worst shock yet, for such men are great moral cowards; and to confront the gentleman they treated so cruelly was so complete a turn, within so short a time, that my words stunned them.

In a quarter of an hour after they were standing before Mr W n. “ Are these your men ? ” said I. “Ah, I know them too well,” said the gentleman. “And I wish I had never seen them; for I am a

stranger here,—all my money is gone, and I know not what to do.”

“ We have none of your money,” replied Stevenson, growlingly.

No doubt secreted somewhere. I forgot to say I searched them at Goodall’s. “ And it is gone, then ? ” said Mr W n, despondingly. “No,” said I; “not all. The money may not be recovered easily, but I will get the watch.” “ Well, I shall live in hope,” said Mr W n, as he went away, leaving his address. They were now locked up, and the next question for me was how to get the property. On the following and subsequent days every effort was made. There had been no pledging or selling to the brokers, and I was at fault; but I had succeeded in so many cases where there appeared no hope, that I persevered. As a last resource, I had a young fellow confined for a short time along with the prisoners, who I knew was on terms of intimacy with them. All thieves and robbers “ split ” when in trouble; confidences are the weakness of criminal natures; yet, perhaps, I would not have got this information if he had not expected I would favour him. He told me that the two men, after having committed the robbery, flew along St Mary’s Wynd, and never stopped till they got to the Dumbiedykes;—that there they placed the watch, sovereigns, and rings into a hole of the old dyke, where they made a secret mark, only known to themselves. I was now as much at fault as ever. The men remained obdurate, and they alone knew the secret. I would, however, try the old dyke; and while I was busy peering into the crevices, who should come up to me but one of the park-keepers?“ I think,” said he, “ I know what you are looking for. You’re Mr M‘Levy? ”

“ Yes,” said I. “ I am searching for a stolen watch and sovereigns; can you help me to the place?”

“ I can, at least, help you to the watch,” said he, as he held out the glittering object, with its gold chain and seals. “ I found it here,” he continued, going a few steps along. “ The rainy night must have washed away the earth from the top of the dyke, for I found it nearly exposed in a hole not deep enough to escape observation.” And so the watch was recovered, but no more. The sovereigns were never found, and are likely in that dyke to this day, for all the three prisoners were shortly after transported for seven years.

References

- Richard Weaver – evangelist who spoke in Edinburgh in 1860 ↩︎

- looking glass – mirror ↩︎

- cully – one easily tricked ↩︎