On going up to the office one day, about eighteen years ago, I was beckoned into his shop by Mr Davidson, hardware-merchant in the High Street. He seemed to have something to say to me of a very mysterious nature, for he took me ben to the back-shop, and shut the door. As for all this, and the long face, I pay generally little heed to such things, for I often find there is but small justification of the mystery inside the heads of long faces; yet I will not say whether in this case I was disappointed or not in my expectations. “ Do you know,” says he, “ there’s a circumstance occurs in my shop, almost every day, for which I cannot account ? ” “Silver disappearing from a till — a very common occurrence, according to my experience.” “ No,” said he; “ pewter is the metal.” Then, drawing closer to me—“There is a youngish woman, and rather interesting, with a mild, innocent look about her, who has come to the shop for a considerable period, always purchasing an article of the same kind.” “ You don’t sell picklocks ? ” “ No, nor is it anything in that way. To be out with it at once, it is a pewter spoon; and not being over particular in noticing either purchaser or purchases, I doubt if I would have remarked particularly even three or four returns; but she has been here almost every other day for months, gets the one solitary spoon, lays down the money ” “ Which, of course, you examine? ” “ Goes away; nay, I have known her to come twice in -one day for the spoon. The only construction I have been able to put upon the mysterious transaction, and even that appears to myself absurd, is, that she is abstracting, one by one, silver spoons out of some platebox, perhaps in her master’s house, and replacing each silver spoon by a pewter one, to keep up the weight and apparent number.” “ More ingenious than sound,” said I. “ I confess that myself, and therefore am I thrown back to my wit’s end.” “ And not far to be thrown, in the direction of the nature of women,” said I. “ It is a far deeper affair than even your supposition.” “ Well, I am dying to know.” “ And will know before dying, but not till perhaps the day after tomorrow, that’s Thursday—or Friday— it may even be Saturday j but know you will. Do you expect her to-day? ” “ Scarcely, as she was here yesterday, Monday. Her double purchases are often on the Saturday.” ‘ “ Not ill to account for that,” said I. “ You may look for her to-morrow, according to her routine. I am ambitious to make acquaintance with her, and shall walk opposite your shop to-morrow forenoon to wait for her. How is she dressed? ” “ Always with the same shawl and bonnet.”

“ The ribbon is a good head-mark.” “ Well, it is orange, the bonnet a chip, and the shawl a Paisley one, white, and a conch-shell border.”

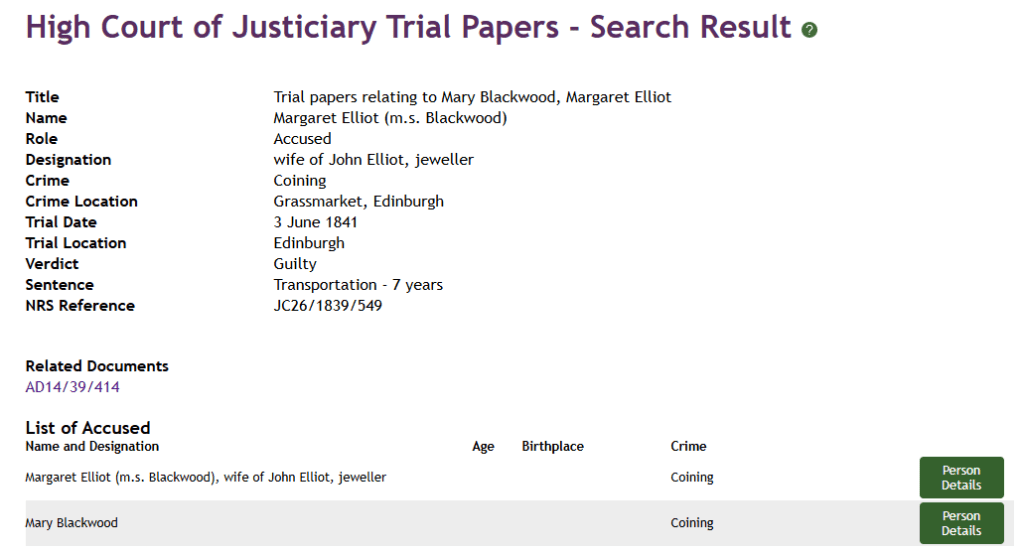

“ A sharp colour orange,” said I, curious as I am in these studies; “ it even disturbs me, it is so penetrating. A woman like this could have nothing to do with green, and yet there is a verdancy about her; where, you won’t guess.” “Where?” “ Why, in the absurdity of her repeating the dose upon you so often.” “Well, that very circumstance has induced me to think that she can have no improper purpose to serve.” “ You don’t know that vice has a weakness about it. We should always paint the devil with a limp.” “ But, really,” rejoined the good man, “ that woman is so mild, so lamb-like, you know, so ” “ Yes, so like a fallen angel on the boards, that you can’t suspect anything behind the scenes; just so. Well, you understand me—I am opposite your shop to-morrow forenoon? ” “ Say twelve.” « Twelve; and you will be kind enough to come to the door yourself, just as she goes out, so that I shall know my ‘ nymph of the pewter spoon.’ ” Leaving the shop, after thus arranging my net, which is generally not over-wide in the meshes, and as far as possible from run-holes, I proceeded to my other business of the day, scarcely ever recurring to the pewter spoon; nor do I think I would have been paying any compliment to other than very simple people if I had supposed that I saw further into the curious-enough- looking affair than ordinary observers might have done. Yet I was at my post on the subsequent day, pacing the north side of the High Street, on either side of the Scotsman’s stair, and noticing, without looking at, my “ hopefuls; ” many of whom, as they passed, gave a hitch to a side as they suddenly found themselves near me, and yet were ashamed to acknowledge their ingratitude to one who took so much care of them, when it would seem they could not take care of themselves. Among these was a young woman of the name of Maggy Blackwood, yet an old acquaintance. I saw Maggy eyeing me very keenly over about the Cross. It may be doubted whether I could detect the movements of a person’s eye at that distance. I don’t choose to make a question of it, yet I wouldn’t advise any one, with the privilege remaining of wearing a silk neckcloth round his neck, to the exclusion of one of a coarser material and with longer ends than cambric bands, to place much confidence in my in- ability. I had, in short, no doubt Maggy was not only scanning me, but watching my movements. An extraordinary girl that,—her sister as well, nearly of the same age; both acute, and fitted for any business calling for my help. They had in their yet short pilgrimage tried all the games in the outlaw side of human life,—prostitution, pocket-picking, copartnership as sleeping partners with thimblers and card-sharpers, the department of “ fancy girls” to blackleg lovers of the fine arts (of nature),—yet they had even till now passed through all dangers almost unscathed; at least, if burnt once or twice, they contrived not only to cure the wound, but even to conceal the scar. In the midst of all this, too, they had kept up a Siamese-twinship of affection for each other, and a sympathy of mutual resistiveness to the causes that generally so soon bring the career of vicious and dissolute women to ruin and death, of so binding and sustaining a character that, if their lives had been consecrated by goodness, one could not have resisted an admiration for them. The secret of all their success—for success it is to pass through such fires—was cunning, a quality which, like some walking- sticks, does well when green for support or guard, but when dry and old breaks and runs up into you.

No sooner had Maggy got her eye upon me, and seen me turn, than she walked quickly on, as if bent on some very commendable business, but not before I had observed the orange ribbon on the white chip, and the conch-shell border. “ Ah, my nymph of the pewter spoon! ” She had thought I was to come between her and her porridge, and therefore the spoon would be of no use. But was I to deprive Maggy of her spoon! Scarcely so. I stepped over to the office, to save her amiable timidity from the withering effect of my surveillance. I could calculate what time she required to go into Mr Davidson’s, and get her spoon, and be out again. And so, to be sure, it turned out; for, after waiting in the recess of the office-stair for only a few minutes, then going across the street, and placing myself a little deep in the mouth of a close, I had the satisfaction of seeing Maggy coming out of the shop, bowed out to the door by Mr Davidson, the light of whose face came over to me as a signal I didn’t need. There was now little necessity for care, because Maggy was known on the streets; nor, as it appeared, did she and her sister keep her lodgings a very great secret, though they had no desire for calls or respects of dear old friends. All she feared was my observing her enter the shop; yet I saw the prudence of not throwing over her “orange” the shadow of my hemlock, and therefore kept at a distance, still following her, till she disappeared up a stair in the Grassmarket. I did not follow her into her room, because that step was not consistent with my mode of conducting such enterprises.

Bless you, that stair—with it flats looking out through their small eyes to the Grassmarket—and I were old friends; we had secrets of each other, and never thought of being perfidious in our loves and confidences. Even that afternoon, when looking about for a stray beam of evidence of any kind to assuage my thirst of light, as I went home to dinner, I felt an impulse that brought my finger softly on the shoulder of an old woman. “ Who have you living with you just now, Mrs W_____ ?” inquired I. “ Twa lasses,” was the reply.

“ Their names? ” “ Maggy and Bess Blackwood,” she answered at once. “ Have they been long with you ? ” “ A gey while; maybe six months.”

“And how do they live at present ?” rejoined I, as I found her so very pleasant. “ Live! brawly, sir, aye plenty o’ siller; very quiet, and never out till the gloaming.”

“Any men going about them ?” “ Seldom ane; they ’re quite reformed since I kenned them; they even let in a missionary at times, wi’ a gey brown black coat, and a gey yellow white cravat, and after he gaes awa’ the door’s barred, and then I’m no sure but they pray,—only they never said sae,—but what am I to think 1” “ A missionary ? ” said I, rather in a thinking than a speaking way,—no doubt, but what is his mission? I thought, as my mind began to play about the image of the pewter spoon. “ And you think they bar you out that they may not be disturbed in their prayers? ” “ Just sae, for Maggy especially is really very serious, sir; and then, they have a Bible; a queer book for them,ye ken,” “Well, Mrs W said I, seriously, “ I like to see my old pupils take to that book; and to satisfy my- self, I intend to look up to-morrow or next day, between twelve and one. If you see me coming up, you’ll take no notice any more than if I were the missionary himself.” “ Just sae,” replied she, with a kind of wink, intercepted by a look at me, whom she could not understand anyhow, for I was in the humour of gravity before dinner. Having faith in Mrs W____ , I had no reason to expect any interruption in my scheme. My pious ladies would only have more time for devotion, without any impediment to the purchase of the spoon; and it was not till the day after the next that I found myself in the wake of Maggy, with another of the same in her pocket. I allowed her to go home, to mount the stair, to get in to her holy’of holies, and to bar the door if she pleased,—even half-an-hour more, just the time required for arriving at the middle of the use to which the pewter spoon would be applied, but cruelly allowing nothing for the ripening of the fruits left by the missionary with the brown-black and the yellow-white. At the end of that period, I went quietly, in my usual manner of the “ taking-it-soft,” up the stairs, put my finger as gently on the latch,—no bar then,—and introduced myself to the devout spinsters. I confess, I took no notice of the start and confusion into which I had so unceremoniously hurried them; but, casting my eyes round, I placed my hand upon one of a row of seven shillings laid up on the cross spar of the top of the bed— “ Tempting, Maggie, but hot,” I said, as my hand recoiled from the touch of the burning coin. “Surely these come from the devil? ”

The two spinsters had by far too much sense to make any protestations, or even excuses for burning my fingers; besides, they were transfixed, “But so rude I am,” I continued, as wheeling round and laying hold of a mould on the cheek of the grate, I turned out the half-impressed last coin, “ I have even interrupted industrious women in ‘ the turning of a shilling.’ ” “No use for your mocking mildness,” said Maggie, as she bit her thin lips, which she could not have bled for her biting, where there seemed no blood—so white they were. “We know it’s all up, but I would rather a hundred times your sneers were damning oaths.” “And so would I,” said Bess, whose words choked her.And who should appear at that moment but he of the missionary vocation t but a most useless servant of his master; for if ever there was a time when his pupils stood in need of consolation it was now; and yet the very instant he saw me, he cried out, “ M’Levy—the devil! ” and bolted without leaving us a blessing ! If he knew me, I also knew him. Having no assistant at the time, I could not follow him with more than my regret that he thus-shied an old benefactor, for I had sent him on a mission to Botany Bay to learn good behaviour; but he returned, to take up the quadruple trade of a fancy man to my two nymphs of the pewter spoon, the utterer of the said spoon in the shape of shillings, the religious cloak of their knavery, and a most successful clerical beggar at the houses of the New Town, of small helps to widows in the Cowgate, dying amidst the cries of their famishing children. Yet I had occasion to overcome my anger some time after, by heaping burning coals on his head, in the form of a new mission to Botany Bay. I even did more, by sending out to the same place his two lovers before him, that he might not be without friends on his arrival, nor for seven years afterwards. But I am anticipating. When the shillings and the young women had cooled down so as to be fit for handling, I removed them to a safe lodging, and then went to dinner. In passing Mr Davidson’s shop I gratified a whim:— “What did Margaret Blackwood pay you for each spoon ? ” said I. “ Threepence.” ’ “Cannot be, or you must be a very bad judge of the value of pewter.” “Why?” “ Because, see there are eight shillings made of one spoon, and supposing you had sold her forty, you have given for ten shillings no less than £16.” “Ah !” said he laughing ” I see I have been a little spooney1.”

- spooney – silly, foolish ↩︎