Miss Balleny, a maiden lady with considerable means, and advanced in years, occupied a first flat, with front door, and an area flat beneath, in Buccleuch Place.

From some peculiar choice, it would seem, and not from necessity, she kept no regular servant, employing a woman to come occasionally, and do any duties she could not herself perform; nor is it thought she had any extreme penuriousness in her nature, that led to this choice; rather, it would seem that she preferred being alone, having discovered perhaps that the Edinburgh servants are not remarkable for either fidelity or affection towards their employers. It is certain, at least, she was an inoffensive lady, and in many respects amiable and kindly in her feelings.! One night, in February 1845, she was preparing to retire to rest, it being near ten o’clock,—seriously disposed, she had been reading her Bible, and engaged in those thoughts that become one of her years. It has often been remarked, as a strange fact in the economy of nature, that the nearer to a catastrophe, the further the thoughts from it—a kind of security into which we are lulled by a false quietude, betokening a continuance of that peace which we could have wished to be un- broken, and which at least might be expected by those who desire to be in friendship with all men. She was startled in the midst of her lonely musings by a noise, as if some one was endeavouring to force an entry through one of the windows of the lower or area flat. Greatly fluttered, she groped her way to the lobby, which ran from the front area-door to the back, and before she got half-way along it, she encountered a man. Giving a suppressed choking scream, she retreated towards the kitchen, where, being followed by the man, he seized a heavy poker, and struck her a terrible blow on the head.

This, with all its severity,’had not it would seem deprived her of sense, for she had set forth such a yell of agony, that it was heard by some of the neighbours. I have heard it said that the intention to kill is rather confirmed and made furious by a thrilling cry—a species of resistance which, expressing horror, is felt by a murderer as an impeachment of his cruelty, besides rousing his fears of being detected; and it is thought that the cruel man was thus roused, for he laid on blow after blow, till the head of his victim bore cuts to the bone as the bloody traces of the terrible onslaught. A single minute or two sufficed for the work—the woman was bathed with blood, and the hand was again raised to put a certain end to life, when an alarm was raised by the neighbours. The poker was instantly dropped, and the murderer, flying along the dark passage, tried the door to the back; it was locked, and he escaped by the window just as the neighbours were at his heels. He got off, but not without being so far noticed, that they could speak to his general appearance and dress. Immediately afterwards, doctors were called, the interest displayed by the sympathisers excluding for a time all efforts at tracing the man. So far as was thought, he had made a clean escape, for the indistinct notice got of him could not have amounted to identification, and the lady, almost at the point of death, could not be questioned, nor, as the attack took place when there was scarcely a glimmer of light, could it be expected she would be able to add much to the vague notice of those who saw him escape. I was at the house next day, but it was four or five days after before I could be permitted to question her; and even then, I found it possible to get only some marks which could not afford me much aid. I ascertained, however, partly from her own lips, in broken accents, and partly from the neighbours, just as much as satisfied me, that the man was a young fellow about eighteen or twenty, and that he wore a lightish moleskin jacket and trowsers. Nothing could be more indefinite, as the dress is that worn by thousands of working men, and the age amounted to nothing. Next day I was in the High Street, not knowing well how to turn, for where, in the wide expanse of the old town, filled with so many dens, and those often crammed with people of all kinds, was I to find the owner of the moleskin jacket and trousers? There were hundreds around me dressed in this common garb : he might as well be among these as in a house, for being certain he was not seen, he would not think it necessary to skulk; and then he had taken nothing with him by which the crime could be brought home to him. The allusions I have made to chance may tire readers, as well as lay my narratives open to suspicion; yet certain it is, that at that minute, when my eyes were busy surveying the crowded street, my attention was suddenly arrested by one I knew to be a thief, and who wore a moleskin jacket and trousers. I immediately walked after him, and it struck me that his dress looked like as if it had been washed and dried very recently. This made me curious; and as he walked on, I quickened my steps till I came nearer him, so as to have a better view of his jacket. I thought I could perceive blotches here and there, very like as if marks of blood had been ineffectually attempted to be washed out. I became at length so satisfied, that I stopped him. “ George,” said I, for I knew him of old, “ you have got your jacket newly washed; but, oh, man, it’s not well done.” “What do you mean ?” said he.

” Why,” said I, “ you have forgotten to rub out the stains of Miss Balleny’s blood.”

In an instant every trace of blood was absent from his cheek, however it stuck to his moleskin—yes, he was instantly pale, and struck dumb.

“ Come,” said I, “ I wish to examine those marks better, and I would rather make the investigation in the office.”

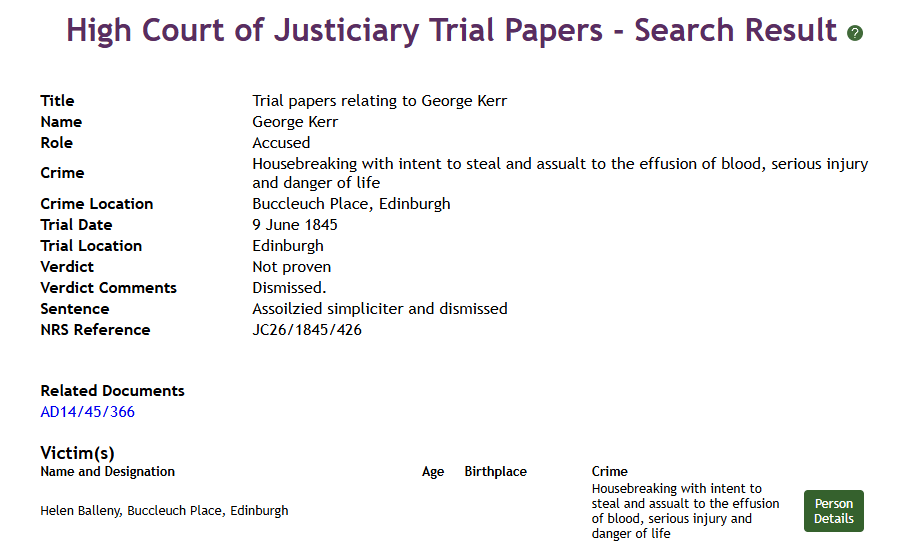

I accordingly took him there, in the midst of all the ordinary protestations and threatenings, and soon got my suspicions confirmed by the opinions of others. As soon as Miss Balleny was supposed to be able to stand the look of him, he was taken to her bedside. I shall never forget the look of that lady, as she brought her nervous eye to bear upon the man who was supposed to be he who did all that bloody work upon her. A shiver seemed to run over her whole body, as if the sight had brought back to her the terrible feelings of that lone and dark hour. It seemed that there had been some glimmer, either from the kitchen fire or from the street lamp through the window, I forget which, but there had been enough to enable her to distinguish his dress and general appearance ; for, after gazing at him for a time, she said, “ 0 God, that is the very man ! ” We afterwards got some of the neighbours to add something like identification, and we thought we had enough, with the blood- stains, to authorise a conviction. The Crown officer having got all the evidence that was to be had, George Kerr was brought to trial before the High Court for the attempt to murder and the housebreaking. Miss Balleny was put into the box as the principal witness; but it became soon apparent that the poor lady had suffered too much to permit of the continuance of that recollection which had served on occasion of the prior meeting. Her mind was gone.

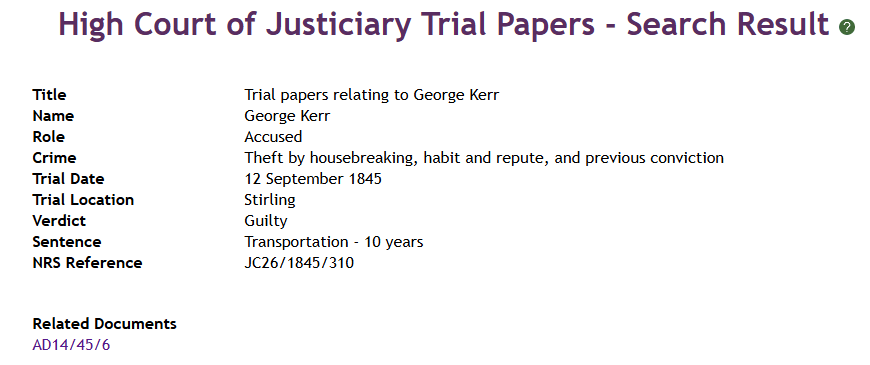

At one time she was positive, at another only suspicious, at another doubtful, only to be more positive again, as the changing thought flickered through her brain. The other witnesses were decided enough as to the dress and generalities; and the washed blood-stains were as decidedly spoken to as marks of such a kind could be; but the fatality lay in Miss Balleny’s incapacity ; and the jury, after a discriminative charge, brought in a verdict of “ not guilty.” All my efforts had thus gone for nothing; but my pride of detection was hurt, and I felt much inclination to stick by my man. I accordingly ascertained that he had gone by the boat to Stirling; and though he had thus left my bounds, he did not take with him my desire to look after his welfare. Nor was it long before my kind demon helped me in my solicitude, for a day or two afterwards the Stirling authorities sent us information that the shop of a Mr Meek had been broken into, on that very evening Kerr had left Edinburgh, by a young man answering to his description, and a sum of money, as well as a silver watch, had been abstracted as booty.

It was now my duty to watch again for my man, though I had small hope he would return so soon to town; nor did he. He had gone direct to Glasgow, with the view of getting the silver watch disposed of at a pawn-shop. There he was signally unfortunate, for the Stirling authorities had sent a description of the watch and the man to the Glasgow police, who had spread the intelligence among the pawnbrokers. Accordingly, when Kerr offered the article at a pawn-shop there, the man to whom it was presented declared immediately that it was stolen, and, sliding between Kerr and the door, endeavoured to detain him. The effort was vain. Kerr darted past him, and outran his pursuers. Of all this we got timely knowledge, and now I had another chance. Always keeping the moth-instinct in view, I suspected that he would be back to his old haunts; and in this case I was made more than usually hopeful, in counting that the money taken at Stirling must have been spent, and the want of wings to fly further would send him crawling to his old nest. My former inquiries had enabled me to know that his mother lived in Macdowall Street. Thither I went, and some- how or other I felt a kind of certainty that I would find him. I knocked at the door with much confidence, and perhaps, on that account, with much humility and gentleness. Mrs Kerr herself answered, and I remember the conversation— “ Well, Mrs Kerr, have you any one living with you?” asked L

“Nobody, sir.’* “ Quite sure? ”

“ Perfectly sure. I’m a lone woman, and after what has befallen my poor innocent son, I am very miserable.” “And so you may well be,” said I, “ for that was a terrible business; but have you no notion where George is?”

“ No, no. I have never seen him since that day of the trial; and I fancy the poor fellow is so ashamed of having been suspected of murder that he ’ll never shew his face in Scotland again.”

“ And have you no lodgers?” I inquired. “ Not a living soul, sir.”

“ Well,” said I, “ I’ll just step in and sea” “ You are very welcome,” she answered, just in that involuntary way that has told me a hundred times that there is somebody in some place where there is nobody ; and so we often need to act against the rule that a person cannot be in two places at the same time. And passing her, I looked round the place she used

as a kitchen. No concealing place there. I then opened the other room, and saw nobody; nor did I expect, as she had time enough before answering my knock to make any convenient arrangements. “ Here is a closet,” said I. “ No, sir; just a cupboard for odds and ends.” “ Locked,” said I. “ Do you usually lock up your cups and saucers ? ”

“ What I use are in the kitchen,” she replied, getting,

as I saw, alarmed. “ And have you not got the key ? ”

“ No, it is lost.” Ah ! the old story, I thought. “ Well, if it is lost,” said I, quietly, “ it is the more necessary that search should be made for it. You go and get it wliert it was lost.”

“ How could it be lost if I knew where it is ? ” said she, thinking me serious, no doubt. “Why, that is just a curious part of the case,” said I;

“ and another is, that if you don’t go and get it where it was lost, I will get an axe in the kitchen and break open the door.” “ What i do you think my son is there 1 ” said she, in affected wonder. “ Yes,” said I. “ I think his shame has gone off, and he has faced Scotland again. Get me the key, quick, or ” and I made for the kitchen.

“ There,” said she, as she drew it out of her pocket; “ the Lord’s will be done.” And there, upon opening the door, was that blood- thirsty man who had so ruthlessly smashed the head ol the aged lady, who never did him a trace of injury, standing bolt upright in a narrow cupboard, which scarcely permitted him to move.

“Ah ! once more, George,” said I. The fellow absolutely ground his teeth against each other till I heard the very rasping; a scowl sat on his low brow, so demoniac that if I had not been accustomed to such looks it might have made me recoil; and I believe if he had had Miss Balleny’s poker, or any other poker, he would have tried his skill at laying open heads on

my cranium. But for all these indications the cure is unshrinking firmness; and sure I am, if I had shewn a trace of weakness, he would have fallen upon me on the instant like a tiger.

“ There is no use for these looks with me,” said I;

“you know me of old; so take the cuffs kindly, or

worse will befall you.”

“ But, sir,” cried the mother, when she saw her son bound, “ is this never to be ended ? Has George not been tried and found innocent ? ”

“ Yes,” said I. “ But we are informed that he robbed a shop in Stirling that very night after he was released; so you see the trial did not shame him quite so much as you thought.” “It’s a d___ d lie !” burst out the fellow; “I have never been out of Edinburgh.”

“ To that I can swear,” said the parent; for, although she had said, “ The Lord’s will be done,” the mother came back again to lie for her murderous boy. No, no; there is no appeasing of this yearning. I have seen it working in all forms. Even if she had seen those hashes in the head of the poor lady, and the body drenched in blood, drawn by the hand of her son, she could not have stayed that yearning. The moment’s horror would have been succeeded by a tear for the victim and a flood for the murderer. So true what some one said to me once—the mother’s heart is the sanctuary that shuts out all detectives. It even makes sinners of good people, just as if, being the very stuff the nerve is made of, it kicks heels-over-head all the virtues, which are only phantom tilings flickering about in the brain.

I confess here to a weakness. When I was taking my man up to the office, I thought all the world was looking at me. Why so ? Since ever that day I saw the mangled head of that poor lady, the vision had haunted me like a ghost, and, having failed in getting the murderer convicted, the spectre followed me more and more, as if insisting I should bring him still to justice ; so when I walked him up, I thought, It is done now—I have got him, and, though he won’t be hanged, he will be better than hanged, for he must get on the chain and the horrible clogs, and pull his legs after him in Norfolk Island, under a scorching sun, and then he will not be obliged to draw the bloody head after him, for it will follow of its own accord, and every gash will make gobs at him. So we think, and yet I have my doubts whether a man who could bring a heavy poker down with all his strength on the head of an unoffending female—I take the

one peculiar case—is capable of relentance. The softness is not in him. I do not say that God is not able to bring it, but I do say that where such a change comes it must be a miracle. We next sent intelligence to Stirling that the now famous George Kerr was safe in our hands. Meantime we knew that the Glasgow police had sent on the watch there, so that the watch and the watch-stealer would meet opportunely, where Mr Meek could speak both to the one and the other. It soon got known to the Crown agent who it was that had broken into Mr Meek’s shop, and I do not doubt that this knowledge helped to quicken the Stirling fiscal’s wits in making a clearer case of the robbery than the Edinburgh official had been able to do. The trial was fixed for the next Circuit. Every effort was made, witnesses called from Glasgow, and all those ferreted out in Stirling that could say a single word to help so good a cause as bringing so cruel a man to justice. If it had been some years earlier, he might have been tried for his life as a housebreaker ; but as it was, it turned out as well as could be expected. He was sentenced to ten years’ transportation. No case ever gave me more satisfaction than this. The people of Edinburgh had been disappointed by the issue of the former trial, and when it was known that he had been sentenced to transportation for a robbery committed on the day of his liberation, the satisfaction was great, and all the greater that the robbery made sure of the real heartless, incurable character of the villain. Indeed, it is not too much to say that the act was worse than murder, for the lady was so desperately maimed that her recovery, with ruined intellect, was rather an additional evil to that first inflicted.