I have often heard it said that the past part of my life must have been a harassing and painful one; called on, as my reputation grew, in so many cases,—obliged to get up at midnight, to pursue thieves and recover property in so wide a range as a city with 200,000 inhabitants, and with often no clue to seize, but obliged, in so many instances, to trust to chance. All this is true enough ; and yet it fails in being a real description, in- so much as it leaves out the incidents that maintain and cheer the spirit,—for I need scarcely say, that if any profession now-a-days can be enlivened by adventure, it is that of a detective officer. With the enthusiasm of the sportsman, whose aim is merely to run down and destroy often innocent animals, he is impelled by the superior motive of benefiting mankind, by ridding society of pests, and restoring the broken fortunes of suffering victims; but, in addition to all this, his ingenuity is taxed while it is solicited by the sufferers, and repaid by the applause of a generous public. A single triumph of ingenuity has repaid me for many a night’s wandering and searching, with not even a trace to guide me.

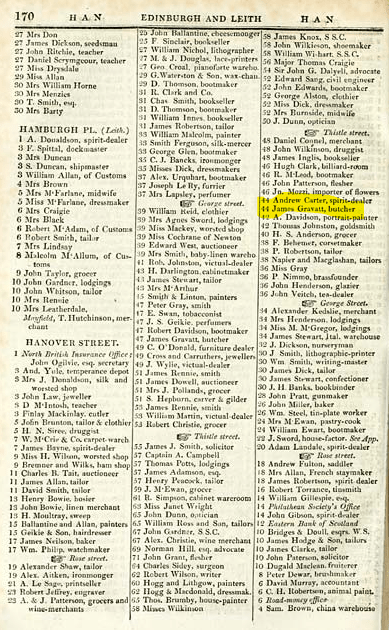

On the 28th of September 1848, the house of Mr Gravat, butcher in Hanover Street, was entered, in the forenoon, by keys, and a large quantity of jewelry and articles of clothing were abstracted. I got immediate notice; and having examined the people who saw the thieves coming out of the stair, I was enabled, from my general knowledge of almost all the members of the tribe —at that time, though only twelve years ago, so much more numerous than now—to fix upon my men. I

have made the cheering remark, “ so much more numerous then than now,” and it is suggestive of a consideration. Society itself has always made its own pests, and it astonishes one to think how long we have been hi coming in to this thought,—nay, it is comparatively only a few years old, as if we had been always blind to the fact, that there are two kinds of thieves and robbers : one comprising those that have no choice but to continue their early habits, got from their parents and associates, and who are wicked from the necessities of their position ; the other, those that are born outlaws. The latter are not so numerous as one would imagine, and though, fiom their natures, independent of any care or culture, could be easily managed. To reclaim them is nearly out of the question; but a speculation on that subject is beyond my depth, my duty being to catch them, and get them punished. But I repeat that I don’t believe they are so numerous as is generally thought. As for the other class, let our Social Science friends just act up to the modern invention of-anticipating the natural wants of human creatures, and the numbers of thieves and robbers will diminish further still. The young men engaged in the robbery I have mentioned were just a part of these pests which we have been making for ourselves, by allowing parents to do what they like with their children,—a privilege we don’t allow to the masters of dogs, which, if they shew a tendency to be dangerous, may be laid hold of before they bite. Yes, Alexander M’Kay, David Hunter, and Thomas Ogilvy, who committed the robbery, and whom I apprehended, would probably have never been in my hands if they had been simply put to a trade, through the medium of a ragged school, or some other mean of that’ kind of benevolence; which is a duty to society itself. I had got my lads,—for men they could hardly be said to be,—but where was the jewelry ? The mere fact of their having been seen coming out of Mr Gravat’s stair was not enough even for a to habit and repute, if it was anything more than a trace to discover them by.

I therefore set about the discovery of the jewels and clothes,—a far more difficult task, if the thieves are cunning, than the seizure of their persons,—and here I found myself at fault; notwithstanding the most unwearied trudging among brokers, resetters, houses of bad fame, and inquiries and searches into even most unlikely places, not a ring or even a handkerchief could I find, so that I was fast arriving at the conclusion that the articles had been “ planked,” as they call it, somewhere, M perhaps in the outskirts of the town, behind a hedge, or under the ground, or in some of the many holes and boles about the old town, left by the gentry, it would almost seem, for the accommodation of their successors.

I must try another mode. I have often succeeded in getting young offenders to be communicative. Though all adepts at using their fingers, they are not all so adroit in using, or rather not using, their tongues. One of the three,—Hunter,—seemed to me to be a likely blabber, if I could once set the instrument a-going. Having got him by himself,— “Now, Hunter,” I said, “I want you to tell me where those things are you and your friends took out of Mr Gravat’s house.”

“Know nothing about them;”—the old story. “Well, I’ll convict you, anyhow,” said I; “a single handkerchief will do the job; you know you have been ‘up’ before, and it don’t take much in that

case.” “But you haven’t got the handkerchief,” said he, as he began to watch my face. “ Don’t be too sure,” I said, as I noticed some sign of his being, at least, apprehensive. “I think you know I seldom fail.”

He was silent, but not dogged. “ I will be your friend,” I continued, “ and make you a witness.” His eye began to gather some light. “ What do you want ?”

“ Just to tell me where the stolen things are, no more.

I don’t want you to confess that you were one of the robbers,”

“ Do you not ? and you will make me a witness ?”

“I think I will manage that for you, if you don’t deceive me.” He thought for a while. “But I wouldn’t have the life of a dog were I known as a peacher1.” “ I’ll take care of you; don’t be afraid, and some thing may be done for you.” Still doubts, and still the terror of being set upon by the gang. I could not help pitying the condition of these slaves to a tyranny that leaves them no chance of penitence or amendment; but seeing the turning-point— the assurance of security—he was easily screwed up, yet I was, by his very first words of disclosure, discomfited. Looking up in my face,— “ It’s no use,” he said. “What do you mean?” I replied, as I noticed something like a mysterious look about him. “ Why, the things,” said he, as if it was a revelation of something very dark, “ are beyond the reach of anyone. Hamilton has got them, and we all know that when he has them they never can be found.” “ That’s Hamilton the hawking broker in the Canongate,” said I. “Yes; but you don’t know,” he continued, “that Hamilton has a secret place in his house, which no man has ever found, and nobody will ever find, where he puts all the stolen articles he gets, and, I tell you, you ’ll never find them.” “Where is that secret place V’

“ I don’t know; nobody knows but himself and his wife.” “ You are certain it is within the house ? ”

“ Yes.” “ And if you cannot tell in what part of the house it is, nor what kind of place it is, whether above ground or under, how do you come to know of it at all ? ”

“ I cannot tell how it came to be known,” said he ; “ all I can say is, that it is a secret among us.”

It now flashed upon me that this man, Thomas Hamilton, had been long able to put us at fault; and the information I now got explained to me his way of doing business. He was thought to be rich, and rich he might well be, from a lucrative trade said to have been so well conducted. He was known to be a hawker

as well as broker, going about the country, and disposing of articles which he could not have exposed in Edinburgh ; and having this secret place of deposit, wherebyhe could, as he so often had done, elude our diligent search, he was always at his ease. I had no doubt he had carried on the system for a long period, and been enabled not only to save a deal of money, but to preserve among the fraternity, or rather sisterhood, of brokers a fair reputation. Taking four men with me to watch, in case, upon my disturbing the secret fountain, some streams might take to ranning outside, I went in upon Mr Hamilton, whom I found in his lower place of business, among those piles of furniture and other things which form so peculiar a feature of a broker’s shop in the Canongate. He knew me too well, and I did not require to tell my errand; yet, though perfectly aware that I had come, as so many had done before, to search his house, he betrayed no fear; if, indeed, he did not appear perfectly indifferent.

“ You are quite welcome,” he said; “ I don’t think

you will find any property here which has been stolen.”

I saw no necessity for a reply to a statement which I was in the habit of hearing every day, and silently commenced my survey through the shop or warehouse. I saw nothing there to take my fancy, though one might have supposed that a mass of furniture was a very good covering for a concealed hole in the floor, and I might recur to that if I failed elsewhere. The only thing that I envied was a hammer lying within reach; and, taking it up, “ Excuse me,” said I. “ You may say so,” said he; “ for I made that except the head with my own hands.” “ Oh, I’ll not injure it/’ I rejoined. He did not seem to understand this proceeding at all, but he never for a moment lost his confidence, if there was not rather a faint smile on his face, just as if he thought, “ Oh, you ’re vastly clever, but I am a head of you.”

I then proceeded up an inside stair, which communicated between the shop and the dwelling-house above, followed by my man, who led me into a sitting room. I expected nothing from a place into which I was led, but I did not object to look about me, which I did very cursorily.

“ Where is your bed-room ? ” I inquired, as I turned and went to a closet door. “ This will be it, I fancy ? ”

“ Ay,” drily, and to me hopefully. On entering, I immediately began, without a moment’s notice, to apply the hammer to the wall, continuing my soundings gradually along over the fire-place, and on the next wall, and on and on till I came to where the bed stood. It had curtains on it,—and here the weakness of vice, as usual, betrayed itself by its whispering revelations : Hamilton became uneasy about his bed, held up the side curtains against the wall, and said, “ Nothing there you see.”

“I didn’t expect anything in the bed, Mr Hamilton,”

said I; “ but please let the curtain fall till I see if the wall is all sound and healthy over the top of the bed, it may come down and bury you and your wife some morning.” A grim smile followed my remark, and I could have read the fate of my enterprise in his face. I continued my soundings, till, after half-a-hundred dull and very unsatisfactory answers, there was one which thrilled through me, and, I have no doubt, Hamilton also. Perhaps he had never in all his life heard any sound so

like that produced by the shovelful of mould on the coffin-lid. Yet, so differently do we estimate things, it was to me more like the ringing of a marriage-bell. “ You ’re not sound here, just at this spot, Mr Hamilton ; and then, to think it is quite over the head of your bed, where you and Mrs Hamilton sleep so innocently after the day’s toil.” On getting a chair and mounting, I observed a slight ruffle on the paper,—a part of that which covered all the four walls,—and, examining still more minutely, I thought I observed a very thin fine crack, appearing as if a knife had been brought along it to the extent of a couple of inches. I then took out a small penknife, Inserted it into the crack, gave it a slight pressure down, and out started a very miniature door, which, on afterwards measuring, I found to be 8 inches by 6. It had a very peculiar and ingeniously-made hinge, on which it went so secretly, that the paper over it appeared to be entire. “A regular pigeon-hole, Mr Hamilton,” said I; “what Is the use of this ? ”

“ I never knew there was such a hole there,” he said; “ it must have been made and left by the last tenant.” “ Who has perhaps left some jewels in it,” I rejoined ; and, putting in my hand, I pulled out a very valuable gold watch. “ A good beginning,” I said, as I laid it on the bed. My next handful was a parcel containing a great portion of Mr Gravat’s jewelry.

“ Quite a pose,” I continued, as I now laid that down; “ there’s no use in people going so far for gold, when one can dig it out here with a penknife.” And, proceeding in the same way with all proper and decorous deliberation, I pulled handful after handful of all kinds of valuable things, from gold time-pieces to tiny rings, till I emptied the large jewel-box and covered the bed. “And now, Mr Hamilton, have you any large box or trunk about you, of small value, which you can lend me for an hour, to contain these things, and then my men will take them up to the Police-office i ’’ “ They must all have belonged to the last tenant,” he persisted in saying, as he turned out to comply with my request. Presently he brought in a chest, and I then called in

two of my men, who soon got the valuables packed, and carried them away. “ There are just two other jewels I want,” said I,—“ you and your wife.” And, calling the other men, we marched the couple —the wife having come in, and been below, wondering what all this work was about—up to the office. The parties were all brought to trial except Hunter. Hamilton was sentenced to seven years’ transportation, and the two lads to eighteen months’ imprisonment. The wife was acquitted on the plea that she was under the command and influence of the husband.

No one can say that the fate of Hamilton was too severe. His resetship was probably not more criminal than others, but the effect, in giving confidence to young men sufficiently inclined to their evil ways otherwise, aggravated his case. I believe that the common remark that the resetter is worse than the thief, and upon which our judges proceed, is correct, if it may not, indeed, be nearly self-evident; for while he in effect makes the thieves, he profits more than they, and besides, escapes their risks of personal danger.

- peacher – an informer ↩︎