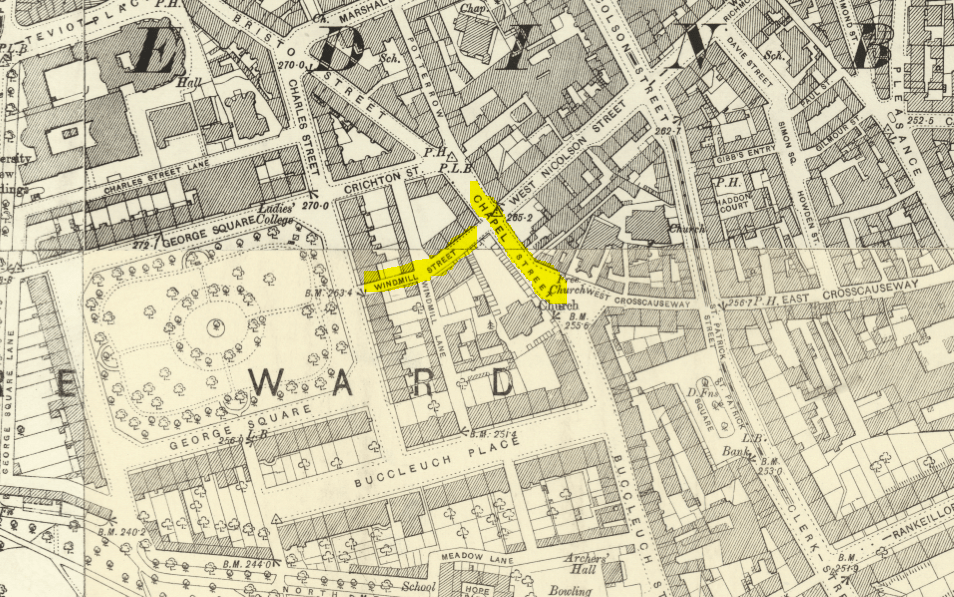

Some time towards the end of the year 1857, I happened to be coming round from Windmill Street to Chapel Street,—musing, of course, as usual; for it must be recollected that we are great students, though having vastly little to do with books,—except sometimes a directory or railway guide. I had got up to Chapel Street a small way, when suddenly a man, bouncing out of a shop occupied by one Flynn, came with a sudden broadside on my left shoulder. No doubt it was an accident; the man was in a hurry, and one don’t mind these things much; but in my case there is this peculiarity, that having always been rather soft in my communication of force, I don’t like to be impinged upon rudely, so I looked sharply round to see my bouncing gentleman, and just met his face as he turned round for an instant to see what effect his jostle had produced. I didn’t know the fellow, but neither did I like his look, which was between the jimmy genteel and the healthy mechanical,—brushed down, and yet frowsy; hat shiny, yet with a dour or two, as if it had met with accidents on the road; buttons on his coat too new to match the threadbare streaks here and there; not yet out at elbows, but coming. Yet all this was little or nothing. There are plenty of such kind of people, who do not qualify themselves for my attention,—a kind of ne’er- do-weels for themselves and ne’er-do-ills for others,— more unfortunate than criminal,—bogles to their friends, and canny towards others. Yet I was struck by this man, principally in consequence of his style of face. Even if I had had no genius in that way, I could not have forgotten it. The principal feature was not like any nose I had ever encountered. It was a straight, sharp line till towards the end, where it bulged out to such an extent at both sides that it looked like a club, and seemed to bespeak pulling as something suited to it and deserved by it. But if this organ was a temptation, there was something above it, in a pair of eyebrows, as well as the squinting lights that shone through them, which seemed to threaten vengeance to the hand that should be so tempted,—just as if that said expression above declared that it had the special care of what so temptingly lay below. Moreover, a scowl at me, who was really the aggrieved party, riveted the impression of features which stood in no need at all of any such auxiliary to make them stick to any mind—far less mine, so ominously retentive of peculiar faces.

I need not say that that face accompanied me, as that of one who was formed of a kind of clay suited to my handling. I could not account for the circumstance that such a person had been resident in Edinburgh for a time, without having thrown out signals to me that he was well worth my acquaintanceship; and the circumstance was the more extraordinary, that the house he came from when he jostled me—to get me, as it would seem, to look at him—was a resort of cardsharpers, perfectly well known to me. Be all that as it may, it is certain at least that the image of that face occupied my mind so exclusively—not only that day and night, but several others—that I fear some other profiles were deprived of that attention from me they deserved; but I was not accountable for this: if God has thought proper to paint “thief,” “robber,” or “murderer” on certain brows, it isn’t for, nothing; nay, it is for something—that the like of me should read the marks, and try to save the good and virtuous from the workings of the spirit which these terrible words are intended to indicate. But if it was certain that I was haunted by that nose so club-like, and those eyes which, being drawn out of the straight course, had got into a twist, from which they could not be untwisted by the eternal regularities of the good and the true,—so calculated as these are to simplify and strengthen vision,—so also was it certain that I entertained no doubt he would fall into my hands, but when, wherefore or how, was of course a mystery. Nay, I was even so presumptuous as to take the jostle, and the consequent shock to my nervous system—not very susceptible that—as a presage of my being to be called upon to protect the rights of society against a man so clearly Cainified to my hand.

Other affairs carried my attentions away in various other directions, but the complexity of these avocations was just no more than a pretty wide meshed net over the surface of a picture, and which scarcely interrupts the view of the piece; and among these calls upon me, a case in Aberdeen, far enough away from Chapel Street, was peculiar and exacting. I am speaking to a period only a few years ago—1857—and the time of the year October. A Mr Lundie, pawn- broker in Glasgow, with a branch doing extensive business in Aberdeen, got his premises in the latter town broken into one night. The affair was not only bold and desperate, but the number of gold and silver watches and valuable jewels of many kinds, was such that the whole of old Aberdeen was on fire. Groups of people stood at the door of the pawn-shop discoursing of the ingenuity of the housebreakers, others were examining the traces of the successful manoeuvre, not only during the next day, but for several days; and, perhaps, there had not been so successful and extensive a depredation in that comparatively quiet town for many years.

Meanwhile the police had their nerves strung up to the mark. The town and suburbs were scoured; and at length two seemly gentlemen, who were so very ill at speaking the Doric of that district, that pure cockney-ism shone through, and declared them to all intents and purposes foreigners, were taken up. What were these southern artists doing so far north? what attraction was there in Aberdeen brose1 over the roast beef of Old England ? in the northern equinoctials over the southern ? Vain questions, for there was no satisfactory answer; but then what right had the Aberdeen police to seize on these curious travellers, merely because a curious case of burglary had taken place in a town not over-pure in other respects—see the Register of Births—besides honesty? Why, no right at all, except that which belongs to a vague suspicion roused by bits of incongruities in dress, appearance, habits, and so forth, not very easily accounted for. So these English gentlemen having broken into the strong box of these suspicions, and, like conjurors, shewn to the astonished police that there was actually nothing under the hat where the pigeon was, got off,—the police acting a little upon the dodge as well as from necessity; for the dismissal, it was thought, would send the adepts to where the valuable booty was planked, with which they would go no doubt south, and be thereby nabbed perhaps by no less a personage than myself.

This trick among us sometimes works very well; and in this case it did not work ill. Information was sent to us in Edinburgh, that the gentlemen would likely pay our Modern Athens a visit, and after a time return to Aberdeen to unplank the plank. We not only got the names,—Thomas Williams and William Thomson,—but also a very graphic account of their persons. Now you will say that my stories have got joints added to them by my fancy; for what were the chances against me of one of these men being my jostler of the club organ’? Not so formidable as you imagine. The secret with me has always been to be about the right place at the right time. What took me up by Chapel Street, but just that I knew that Flynn’s house was to me an interesting one ? and then thieves are wonderfully narrowed in their haunts. If my jack of clubs was to be anywhere, he would be among the cardsharpers at Flynn’s, and a cardsharper does not consider it beneath him to shuffle gold watches in place of bits of pasteboard, if he can play the game with nothing in his pocket for stakes. It don’t signify : the account from Aberdeen was a pen-and-ink sun-picture of my jack of clubs, so well drawn that I recognised him in a moment; nay, for aught I know, he was at that moment when he jostled the wayfarer M‘Levy, and scowled back upon him, on his way to the pawn-shop in Aberdeen, where Thomson was before him, making espials2 and arrangements, in their prudent way.

It was natural that I should wish, by way of revenge, to smile upon that face which had scowled upon me; but, although I considered it very probable that the Aberdeen police were right in supposing that the gentlemen had come to Edinburgh to wait until the plank was ripe for lifting, and do a little by-play at Flynn’s in the meantime, it was not for me to shew my face there, to flutter the wings that were to carry them to my dovecot with the straws in their bills. No ; I behoved merely to set a watch, which I did without any effect; and then came another communication from Aberdeen, —and how the police there got the information I never learned,—that on Friday the 2d of October the burglars had started from Edinburgh for the north, with the intention to remove the booty. So my club had proved a trump over my ace of hearts, and my next object was to watch them when they came south, which they would very soon do. Though, strangely enough, the northern gentlemen of the second sight had come to know what seemed to me almost impossible to be known, they were ignorant of that which seemed likely they would know, that the enemy had again taken a direction towards my beat.

Thieves and robbers observe Sunday;—the blessed day drives them into their dens, where

“Sabbath, shines no Sabbath-day to thieves;”

— that is, as a holy day on which God is to be worshipped, and sins repented of, but as an unholy day so far as their desecration can go. The very sternness of soul which makes them the breakers of God’s law is aggravated and irritated by the sound of the Sabbath bell and the crowded tread of worshippers; for how otherwise can we account for that day being chosen for their hellish jubilees—ay, for the very advantage they take of houses left empty that the house of God may be full ? What then ?—the advantage they think, in their madness, they derive from the observation of the day of peace and rest, we turn round, till the head of the scorpion bites its tail in the midst of the fire of retribution. Yes, we must observe their observation; and so on the next Sunday I expected something which might turn the tables upon them. No more watching of Mr Flynn’s door, where I had been jostled, and where it was now my turn to jostle, but not scowl. I took with me, in the evening, four assistants,—for I knew that meet whom I might they would not, on the Lord’s day, be solitary beings, immured in separate rooms, communing with their spirits in retirement, but congregated in clusters, triumphing over their wickedness, under the sympathetic power of the esprit de corps. Arriving at Flynn’s, I told my men to stand back and be ready for a rush,—perhaps a fight; for my “club” would not turn out a sapling among willows, bleating as the zephyrs blew. I knocked, and the door was opened by Flynn himself, but immediately shut again,—upon my baton interposed close by the lintel. I pushed in, and three of my men followed, with scarcely any noise, the fourth being for the outer escapes.

“ Now,” said I, as I wheeled and took hold of the key and turned it gently in the smooth lock, “ let hush be the word. If you, Flynn, raise a syllable higher than a loud breath, you are up on the instant.”

The man was mute—he could not help himself; and even the wife found a rein to her tongue, somewhere about the back nerves, which are amenable to fear. They remained in the front shop along with the men, who stood guard at the door. I knew the form of the house, and my knowledge of that guided my movements. There was a kind of kitchen adjoining the shop; the communicating door was shut—a good-enough omen. Beyond that there was a room, usually the scene of holiday cardsharping, and off that a dark closet, where I promised myself some light, neither from window, gas, nor candle. I have got light through the points of my fingers before now. So making no noise, I approached the door to the kitchen, opened it upon the instant, and there saw two men busy at a Sunday dinner which would not have shamed the feast church-goers fairly think they are entitled to on the day of rest, after two good sermons—things which I have heard said are appetising, though for what reason I know not. Yes; there was, in his proper person, my master of clubs,—even he who at the door of that shop had been so unpolite as to jostle me, a simple lounger in the streets, and not even so much as looking at him,—and Thomson too; in short, the two English thieves who had taken an affection to the Aberdeen watches and jewels.

“ Don’t disturb yourselves, gentlemen,” I said. “ Eat away; that’s a good roast joint, so well loved in England, and it may be a good long time before you see another.”

The sound of the knives and forks ceased on the instant. They started to run. “ Be seated,” said I; “ there are three valets at the door, ready to wait upon you. So go on with your dinner, for after your run from the north you must be hungry.”

I saw Williams’s eyes fixed on me with that twist. so like the beak of the crossbill, when applying its nippers to a chesnut. I could not tell whether he saw in me the man whom he had encountered so rudely before at Flynn’s door; perhaps he did; and if so, could it be supposed that he possessed a mind from God so strangely formed that it could not by any means work out a rough problem of natural religion, which is often accomplished by blind fear 1 I can’t tell; these things are a foot or ten thousand miles beyond the cast of my plumb; but I can at least say, that as I looked at him, and remembered the extraordinary circumstance of our meeting, I was impressed by a feeling which, if I had not been on my watch, would have turned the black of my eye up under the lid to seek light in darkness.

“ Just remain,” I said again; “ I will be with you instantly, and if you cry, your flunkies at the door will attend to you. There can be no bolting, you know, in spite of bolts. I have taken care of that. So, steady.”

Irony is one’s only weapon where mildness is mocked and sternness resisted. Williams’s scowl got darker, but not more, dangerous, as his hand grasped the knife which he held in his hand; but I knew it would be only the knife that would suffer.

“ There is the hot joint,” said I, as I watched him; “ that’s the mark for the knife.”

And leaving them in that fix,—with the roast before them, which they could not eat, however hungry, and the valets behind them, whom they could not call, except to give them hotter plates than suited fingers fonder of cold gold,—I opened the door leading to the back-room, and there found nine cardsharpers, seated round a table, so busy trying to cut each other as well as the cards, that they had not heard any part of the melodrama in the kitchen or front shop. So much the better; yet, as the window was being looked after outside, I had not much to fear. By several of these I was known.

“ All busy on the Lord’s-day,” I saluted this graceless crew of the darkest and most determined vagabonds on the face of the earth.

And the growl was terrible,—-just as if a kennel had seen Reynard’s nose3 smelling a bit of their dead horse within the ring. I knew the growl would, like the wind, be contented in this case with its own sound; yet I may remark, that thimblers and cardsharpers are a class of men far more dangerous to the person than are the shop-lifters and pickers,—the latter have at least a little of that boldness of character which is not so often found associated with cruelty as you find the dark cunning of the former.

Now, not a single word or sound but that rumbling growl. Nor was it for me to dally with such men by rubbing irony against the sharp file of their wrath. I had another object in view just then. They were safe, and so far I was satisfied. The door leading to the dark closet I have mentioned was a little ajar. I had no light, and did not wish to call for one at that juncture. I had found my way in very dark places before; and, as I have hinted with some weak egotism, my fingers are pointed with phosphorus like lucifer matches. I groped my way,—the more easy that I had groped there before, but not to any good purpose; nor indeed, to say the truth, was I very hopeful even now, considering, as I did, that these men were, as the slang goes, so up, that I could not come down upon them in that easy way,—I mean I could scarcely suppose that that closet would be selected as a planking hole. At the same time, I was aware that the jaunting members of the fraternity (for that the entire inmates in both rooms formed one corps I had no doubt) had newly returned home for a late dinner, and a hungry man likes to satisfy his appetite before he takes out the soiled shirts to be given to wash. So I groped my way, feeling about and about. There were carpet bags hung on pegs round and round. I grasped them hard, not for soft goods, and I know the grip of a watch as well as any man. Nothing there in any of these bags to gratify my touch, yet all the while there was a flustering and whispering among the sharpers, inspiring enough to have given me hope. Was I to be discomfited, and, after all my somewhat confident irony, to be laughed at by these scoundrels in the way they can so well do, giving me a chorus to my song of triumph, like a satirical note at the bottom of a page making a mockery of the text. It was like it; and no one can tell what it is for a detective to be “ done ” by his children careering on the top of a “ fault ” in his scent.

I stood for a moment in the middle of the closet, considering what I should do, whether to carry the hope-less bags out to the light, or get a candle in, when just as I had resolved on the latter alternative, and had brought my right leg round to turn my body to the door, my foot encountered a bag lying on the floor pretty close to the wall,—and oh, that touch of the toe, so much more fortunate than my finger-points ! Nothing but a watch could have resisted so neatly that touch; nay, I could have sworn I had broken a glass, for there followed the impulse just such a pretty tinkle as one might expect from amusical glass—musical to me in my downcast hopes—touched in rather a rough way. My hand was on the object in an instant. I took it up, gripped it, and gripped it again, as doctors do for a knot that should not be among the soft parts; and there I could feel, one after another, thirty or forty of these round resistances, all as well marked in their rotundity as little Altringhams, with shaws too, no doubt.

I had got what I wanted, and presently came out. “ Does this bag belong to any of you gentlemen ? ” I inquired.

No one spoke.

“Will nobody claim it?” I insisted, opening the intermediate door, and taking in the two of the roast- joint interlude within the verge of my appeal. Why are mankind accused of selfishness, and a love especially for such fine things as watches and rings, when we find such an occurrence as I now witnessed can happen among those whose rapacity is said to be born of their very “mother wit ?” Every one of these men denied after another that he had any connexion with or claim to this pawnbroker’s shop in a bag; and with such evidence of self-denial as I thus often encounter, it may well be wondered at that I should not have long ere now given up my unfavourable opinion of mankind. “Well,” said I, “if the bag don’t belong to you, I am certain that you belong to the bag ; and, as the bag must go with me, and as I don’t think that what belongs naturally or artificially to a thing ought to be cut off from it, you will all of you go with the bag to the Police-office.”

Terrible commotion, threats, growlings, scuffling, denials, interjections, “ disjunctive conjunctions.”

“ It won’t do,” said I; “ get your hats.”

And they soon came to their senses. When the time comes, no one can give in more handsomely than an outlaw, so as to become an inlaw, just until he can break out, again to break in, somewhere else than into a police-office or court of justice. In the course of half an hour these eleven gentlemen, with Flynn and his wife, were safely at their “home.” The bag was opened. Let me transfer from my book the numbers:—23 silver watches; 17 gold watches, many of them superb; 170 gold rings, several very rich and of great value; 50 gold chains, many of them massive and weighty. It is scarcely possible to imagine a detective’s feelings on pulling out of a mysterious bag the very things he wants. Even the robber, when his fingers are all of a quiver in the rapid clutch of a diamond necklace, feels no greater delight than we do when we retract that watch from the same fingers now closed with a nervous grasp; or, what is nearly the same thing, draw it out of his bag. Ah, but not the same thing in other respects here. The jewelry was no doubt identified as that of the Aberdeen pawn shop; and, though I assumed that these thirteen belonged to the bag in some way, unfortunately it was only an assumption. And, accordingly, the Aberdeen authorities felt this difficulty.

Nor did it tend to diminish it, that, when we landed at the railway station, we encountered an extraordinary scene. Somehow it had got wind there that the robbers were expected. I have remarked that the robbery had made a great sensation in the quiet town of old Aberdeen. Well, no sooner had we arrived with our charge, than we were met by a perfect scene of triumph. Old Aberdeen seemed to have poured forth all her children that night to witness those adroit fellows who had so deceived the sharp ones of “the Doric order” there. Never was such a scene. Why, it might have seemed that the town was so virtuous that a robbery was as great a wonder there as it would be, or would have been, in that strange country I have heard some speak of,—called Arcadia, I think,—where there are not, and never has been, any necessity for detectives at all. (I think I shall pass the last of my days there, if I knew where to find it.) The whole street, from the station to the Police-office, was crammed with people, all prepared to give us a great reception; and so surely it was, for a louder shout I never heard than that which rose and re-sounded as we passed along with our thirteen prisoners, neatly handcuffed. But, alas! even we have enemies other than our children. Our fathers, the judges and great officers, sometimes think us fast youths. Those “ guv’nors ” are so exacting and fastidious, they don’t go into our humours. They asked proof of the possession of the said bag of gold, and legally no one was responsible for it but Flynn and his wife, who, though the custodiers thereof, denied that they had any knowledge of it; and then they were no more amenable to justice than the innkeeper is who is found to have in some bed-room of his premises a golden waif or drift-cast, brought there by whom he knows not.

Those men, of whom I had taken so much care, were accordingly taken from us, and let off, to plunder the lieges, and I was left with the sole consolation of having recovered some, £300 or £400—all for a pawnbroker, who ought to have taken better care of his pawns. A conviction of my “ club” would have repaid him for the jostle he gave me. I am in his debt to this hour, though I have no doubt he could not be got anywhere now in this hemisphere to give me a proper discharge. This case is, therefore, more a confession on my part than a detection. I don’t like it much,—it goes against the hair, and brings sparks of anger, not altogether consistent with my incombustible nature. The club nose, however, remains; and who knows what may happen before I go to Arcadia4?

- Brose is a Scots word for an uncooked form of porridge, whereby oatmeal (and/or other meals) is mixed with boiling water (or stock) and allowed to stand for a short time.. ↩︎

- espial – to keep watch ↩︎

- “Reynard’s nose” refers to Raynaud’s phenomenon or disease, a condition causing reduced blood flow to the fingers and toes, often in response to cold or stress. It’s named after the French doctor Maurice Raynaud. ↩︎

- Arcadia – utopia ↩︎